Visualize the images of “mission control” that you might have seen as part of any space shuttle launches or a scene from the movie Apollo 13. Another good image to conjure would be the “bridge” from the starship Enterprise in Star Trek.  In each of these images you have a similar underlying idea of a location where a massive amount of “sensory” data flows into a command center. Advanced technology and highly skilled resources review every bit of data that is possible to capture, scanning the data stream for any anomalies or patterns. Once something “blips,” attention is immediately focused on that aberration and a reaction is mounted:

In each of these images you have a similar underlying idea of a location where a massive amount of “sensory” data flows into a command center. Advanced technology and highly skilled resources review every bit of data that is possible to capture, scanning the data stream for any anomalies or patterns. Once something “blips,” attention is immediately focused on that aberration and a reaction is mounted:

“Captain, they’re raising their shields!”

What happens next is immediate: “Red Alert”

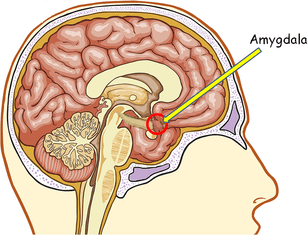

There is a structure in the human brain called the amygdala. It is part of what is known as the limbic system. The amygdala is located in the temporal lobe of the brain – in close proximity to the brain stem.

There are some who refer to the amygdala as the fear center of the brain; it is considered by others to be the emotion-processing center of the brain. I like to consider the amygdala “mission control” or, maybe more accurately, a “strategic command center.”

It is the amygdala that signals “Red Alert” in the brain. The amygdala is the emergency management system in the brain using to separate pathways of response. The amygdala is the initial, immediate, instantaneous response to anomaly.

There is also a data stream to the amygdala’s mission control that links through the sensory cortex of the brain. This secondary data stream provides the problem-solving associated with the “red alert.”

To give some context to how the amygdala processes and responds to the data that streams through it, let’s talk about a walk I took through a nature park near my home. It was a balmy late-summer day. Beautiful clear skies and roughly eighty degrees – it was a perfect day for a walk on the asphalt path of the park.

As I was strolling through the path, enjoying the beauty of the gorgeous day, my attention suddenly snapped to an object that had been laying on the edge of the path as it began to stretch itself out across the width of the path. My immediate reaction was to stop. It took a millisecond or two longer for my brain to grasp that it wasn’t a stick that was moving, it was a snake! I took an instinctive step backwards away from the snake as I was observing how long it was before I remembered that I live in a part of the world where few poisonous snakes are found outside zoos and pet stores. I then took a step closer to see if I could capture a picture of the reptile with my cellphone because I didn’t recall that garter snakes could grow to three feet in length.

My amygdala was responsible for the immediate snap of my attention to the unexpected movement on the side of the path, the immediate stop and my step backwards: Whoa – stop – safe distance!

The curiosity and inquisitive action that occurred once my initial startle had passed reflected that my amygdala had moved from the immediate “survival” response into processing through the sensory cortex which transformed my initial surprise into an investigative process. “What is that?”

Another good example of this blended pathway of sensory processing would be an adult’s response to a loud noise. An explosion occurs, your amygdala has you “jumping” and turning your head in the direction of the sound before your eyes, ears, and nose are reporting that the car next to you backfired.

The amygdala generates the “Houston, we have a problem” response. The sensory cortex pathway brings forth the investigative team: what was that? What direction did it come from? Have we seen this before? Who is involved? Etc.

All incoming stimulus – visual, auditory, tactile, spatial – is processed through the amygdala. There is a constant stream of data flowing through – even when you are not conscious of it. In all truth, the amygdala is reviewing this stream of data particularly when you are not conscious of it.

Is anyone reading this asking themselves why I would be including this information in a blog about addiction and recovery? I’d love to hear your thoughts…